11 Things from the week | 21 Jun 25

News from the past week, and a few other things.

1. Updates on Israel and Iran

NOTE: Below are a few resources which provide updates (strikes, maps, and more) on Israel and Iran.

Tracking the Israel-Iran war (Economist)

The conflict between Israel and Iran continues to escalate. In the early hours of June 13th Israel launched a series of strikes against Iran, targeting nuclear sites and missile facilities as well as military commanders and nuclear scientists. Binyamin Netanyahu, Israel’s prime minister, said the attacks—named “Operation Rising Lion”—aimed to disable Iran’s nuclear programme. Since then, the countries have exchanged waves of strikes: Iran has launched ballistic-missile and drone strikes at Israeli cities; Israel has hit further military facilities, nuclear plants and oil-and-gas infrastructure.

Mapping the Israel-Iran Conflict (NYT)

New York Times analysis.

Institute for the Study of War and Critical Threats Project

The Critical Threats Project (CTP) at the American Enterprise Institute and the Institute for the Study of War (ISW) are publishing multiple updates daily to provide analysis on the war with Iran. The morning update will focus on the exchange of fire between Iran and Israel. The evening update will be more comprehensive, covering events over the past 24-hour period and refining items discussed in the morning update.

Council on Foreign Relations

The United States maintains an extensive military footprint in the Middle East, including a number of naval assets and permanent U.S. bases. Washington’s presence has allowed it to respond to regional threats, including the Yemen-based Houthi rebels and escalating Israel-Iran tensions.

Jewish Institute for National Security of America (JINSA)

The Jewish Institute for National Security of America’s (JINSA) Iran Projectile Tracker presents regularly updated charts and graphs on missiles, rockets, drones, and mortars that Iran and its regional proxies have fired at U.S. personnel, partners, and interests in the Middle East.

Economy

2. The Path to Record Deficits (WSJ)

Take a spin in the time machine, back to an era when the federal budget deficit didn’t look like a problem at all.

In 2000, the federal government actually ran a surplus and the Congressional Budget Office, Capitol Hill’s nonpartisan scorekeeper, projected the Treasury would keep collecting enough revenue to pay for all government programs and generate continuing surpluses.

Fast-forward to 2025, and the U.S. is running record deficits outside of wars, recessions or crises. The nation’s publicly held debt is nearing 100% of gross domestic product and is projected to surpass the post World War II record of 106% in a few years.

What happened? It wasn’t a single event but a mix of factors: an aging population, tax cuts, wars, the 2008 financial crisis, expanded healthcare spending, the Covid-19 pandemic and rising federal assistance to households. Both parties played a part. Democrats did little to reverse that tide of red ink when they controlled Congress and Joe Biden was president. Now, Republicans and President Trump are pushing a tax-and-spending megabill that would add trillions to deficits, compared with letting tax cuts expire as scheduled. Here’s a look at how we got here.

NOTE: Great interactive article by WSJ showing the past 25 years of the CBO’s moment-in-time forecasts versus what actually happened.

A summary of how we got here:

Overspending: wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment act to make up for the 2007-2009 recession, emergency legislation to make up for COVID-19 impacts, higher interest costs, higher entitlement spending

Tax revenue shortfall: Multiple tax cuts, 2007-2009 recession, COVID-19

3. Social Security’s Potential Insolvency Date Moves Up One Year (WSJ)

With an aging U.S. population and a smaller share of American workers who pay into it, Social Security could become unable to pay full retirement and disability benefits in 2034, one year earlier than reported last year, the program’s trustees said Wednesday.

The Social Security outlook worsened for several reasons, according to the report. Notably, in a bipartisan vote, Congress changed benefit formulas in a way that is providing more money to certain public-sector workers, including many teachers, firefighters and police officers.

In many cases, those retirees had faced limits on benefits because they worked for part of their careers in jobs outside the Social Security system. In addition, the government adjusted its expectations for fertility rates.

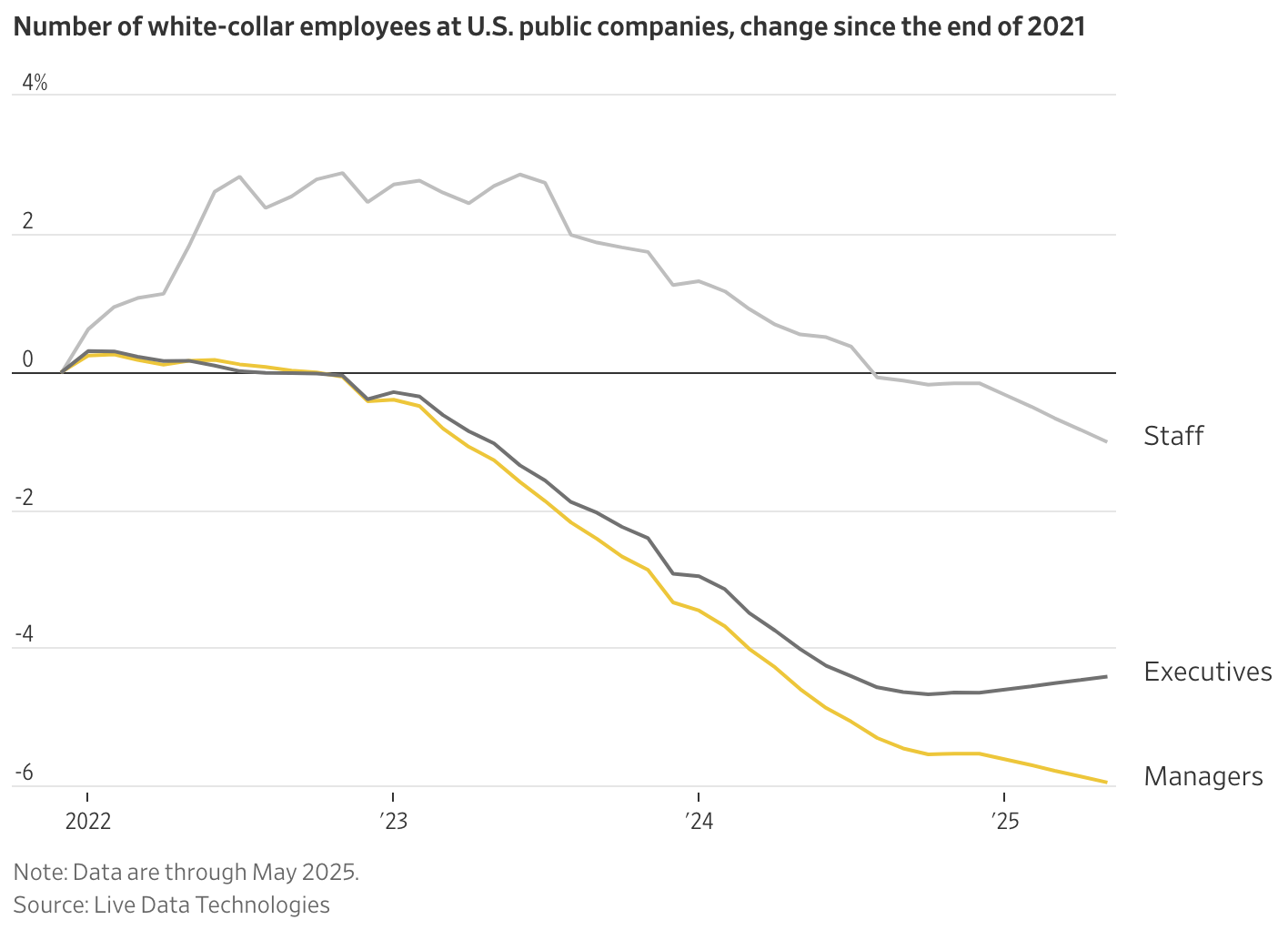

4. The Biggest Companies Across America Are Cutting Their Workforces (WSJ)

U.S. public companies have reduced their white-collar workforces by a collective 3.5% over the past three years, according to employment data-provider Live Data Technologies. Over the past decade, one in five companies in the S&P 500 have shrunk. New technologies like generative artificial intelligence are allowing companies to do more with less. But there’s more to this movement. From Amazon in Seattle to Bank of America in Charlotte, N.C., and at companies big and small everywhere in between, there’s a growing belief that having too many employees is itself an impediment. The message from many bosses: Anyone still on the payroll could be working harder.

The downsizing has caused employees to rapidly lose the leverage they enjoyed during the pandemic, when jobs were plentiful and companies were bidding up for white-collar talent. Even with AI advances on the horizon, many corporate leaders and labor economists have projected long-term shortages in both salaried and hourly jobs.

Companies’ flattening has left managers leading larger teams. In 2020, managers had an average 4.2 direct reports, according to Lattice, a human-resources software provider. By 2023, that number was 5.1

5. Factory work is overrated. Here are the jobs of the future (Economist)

For years, politicians and some economists have linked manufacturing’s long decline to stagnant wages, hollowed-out towns and even the opioid crisis. In the 2000s alone America shed nearly 6m factory jobs. Such work often offered high-school leavers a route to a stable, quietly prosperous life. It sustained entire cities, earning Pittsburgh the moniker “Steel City” and Akron that of “Rubber Capital of the World”. Little surprise, then, that politicians across the spectrum want the jobs back.

Yet there is a problem: even if industry returns, the old jobs will not. Manufacturing produces more than in the past with fewer hands—a transformation much like that undergone by agriculture. Accessible, middle-class work of the sort that once drew crowds to the factory gates in America’s Fordist heyday has all but vanished. According to our analysis, the most similar work to the manufacturing jobs of the 1970s is not to be found in factories, which are now automated and capital-intensive, but in employment as an electrician, mechanic or police officer. All offer decent wages to those lacking a degree.

Whereas almost a quarter of American workers were employed in manufacturing in the 1970s, today less than one in ten is. Moreover, half of “manufacturing” jobs are in support roles such as human relations and marketing, or professional ones such as design and engineering. Less than 4% of American workers actually toil on a factory floor. America is not unique. Even Germany, Japan and South Korea, which run large trade surpluses in manufactured goods, have seen steady declines in the share of such employment.

As countries grow richer, automation raises output per worker, consumption shifts from goods to services, and labour-intensive production moves abroad. But this does not mean factory output collapses. In real terms, America’s is over twice as high as in the early 1980s; the country churns out more goods than Japan, Germany and South Korea combined.

A job in industry is also now harder to attain. Modern factories are high-tech, run by engineers and technicians. In the early 1980s blue-collar assemblers, machine operators and repair workers made up more than half of the manufacturing workforce. Today they account for less than a third. White-collar professionals outnumber blue-collar factory-floor workers by a wide margin. Even once obtained, a factory job is far less likely to be unionised than in previous decades, with membership having fallen from one in four workers in the 1980s to less than one in ten today.

Over 7m Americans work as carpenters, electricians, solar-panel installers and in other such trades; almost all are male and lack a degree. The median wage is a solid $25 an hour, unionisation is above average and demand is expected to rise as America upgrades its infrastructure. Another 5m toil as repair and maintenance workers—think HVAC technicians and telecom installers—and mechanics, earning wages well above the factory-floor average. Emergency and security workers also show similarities; over a third are union members.

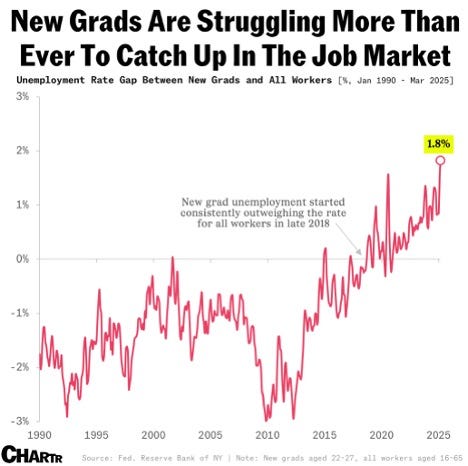

NOTE: Last week I provided the chart below showing overall unemployment rates for recent college graduates. This week, a few more articles came out on this topic.

6. Young Graduates Are Facing an Employment Crisis (WSJ)

The U.S. labor market is holding steady despite extraordinary economic upheaval. But it is a bad time to be a job seeker—especially if you are young.

Recent college and high-school graduates are facing an employment crisis. The overall national unemployment rate remains around 4%, but for new college graduates looking for work, it is much higher: 6.6% over the past 12 months ending in May. That is about the highest level in a decade—excluding the pandemic unemployment spike—and up from 6% for the 12-month period a year earlier.

That rate, based on data from the Labor Department, applies to people ages 20 to 24 looking for work who have at least a bachelor’s degree. (This group is mostly people 21 to 24, since few people graduate college sooner.)

Young graduates typically face a higher unemployment rate than their counterparts who have been in the workforce longer, but the gap is growing wider between older workers and the young.

Moreover, the gap between the unemployment rate for these young graduates and the broader population became its widest in about 35 years of comparable New York Fed analysis.

7. Home Flipping Profits Drop in First Quarter (ATOM)

Home flips, as a share of total sales, rose quarter-over-quarter in 76.3 percent (132) of the 173 metropolitan statistical areas with sufficient data to analyze. However, the share was down compared to the same time last year in two thirds (115) of the metro areas. Metro areas were included if they had a population of 200,000 or more and at least 50 home flips in the first quarter of 2025.

Artificial Intelligence

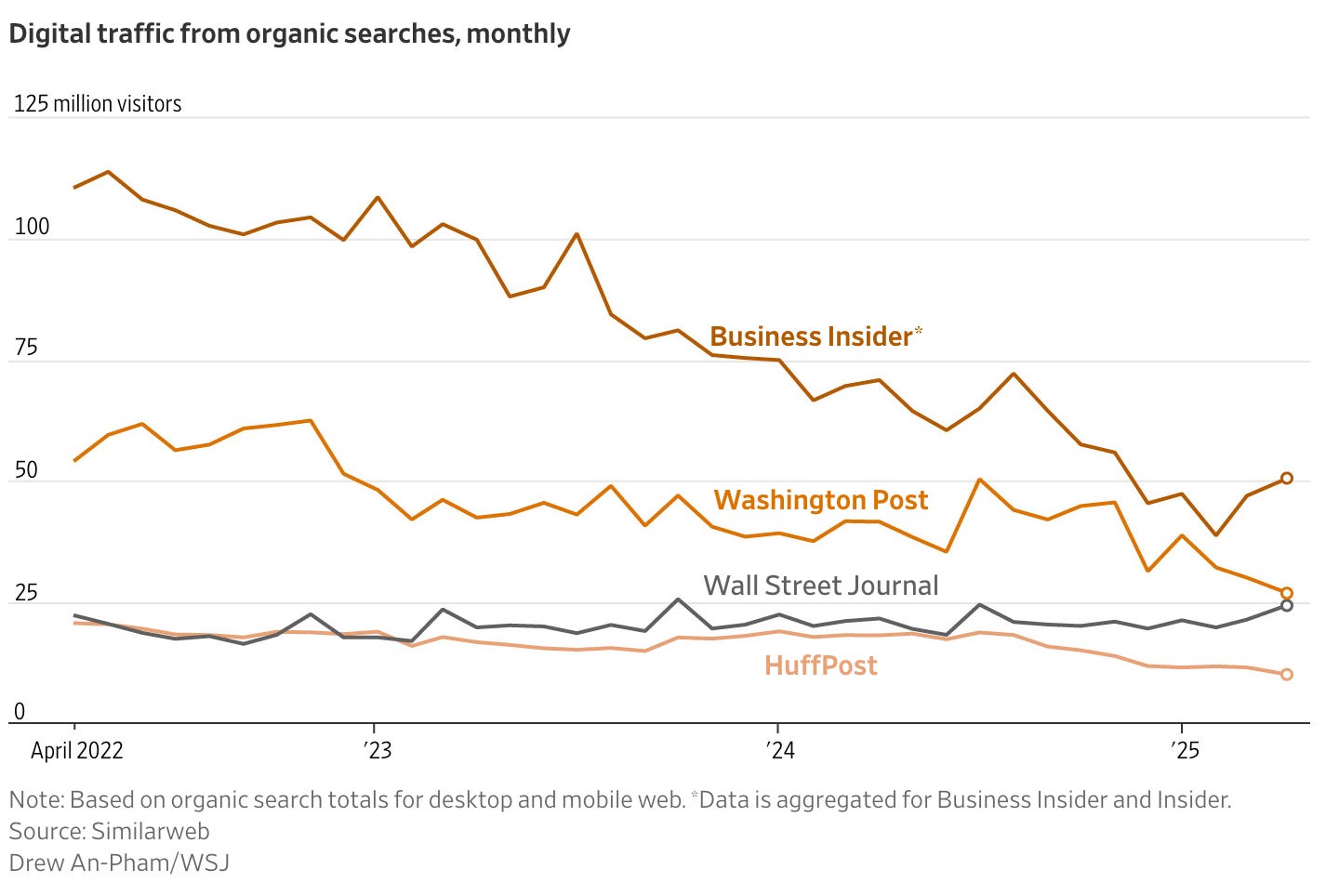

8. News Sites Are Getting Crushed by Google’s New AI Tools (WSJ)

The AI armageddon is here for online news publishers. Chatbots are replacing Google searches, eliminating the need to click on blue links and tanking referrals to news sites. As a result, traffic that publishers relied on for years is plummeting.

Traffic from organic search to HuffPost’s desktop and mobile websites fell by just over half in the past three years, and by nearly that much at the Washington Post, according to digital market data firm Similarweb.

Business Insider cut about 21% of its staff last month, a move CEO Barbara Peng said was aimed at helping the publication “endure extreme traffic drops outside of our control.” Organic search traffic to its websites declined by 55% between April 2022 and April 2025, according to data from Similarweb.

At a companywide meeting earlier this year, Nicholas Thompson, chief executive of the Atlantic, said the publication should assume traffic from Google would drop toward zero and the company needed to evolve its business model.

Entertainment

9. Hit songs are getting shorter (Economist)

Of the songs that Spotify, a streaming service, reckons will “take over the summer”, half are under three minutes. Yet The Economist’s analysis of almost 1,200 number-one hits suggests brevity is not season-specific. The average length of songs that top the Billboard Hot 100 has decreased by around 18%, from four minutes and 22 seconds in 1990 to three minutes and 34 seconds in 2024 (see chart). Songs are the shortest they have been since the 1960s. The mentality, summed up by Jennie, a South Korean artist, is: “Don’t bore us, take it to the chorus.”

Religion

10. The West has stopped losing its religion (Economist)

FOR DECADES America’s fastest-growing religious affiliation was no religion at all. In 1990 just 5% of Americans said they were atheists, agnostics or believed in “nothing in particular”. By 2019 some 30% ticked those boxes. Those who left the pews became more socially liberal, married later and had fewer children. Churches, where once half of Americans mingled every Sunday, faded in civic life. Yet for the first time in half a century, the march of secularism has stopped (see chart 1).

The same is true elsewhere. In Canada, Britain and France, the share of people telling pollsters they are irreligious has stopped growing. Across another seven western European countries it has slowed markedly, rising by just three percentage points since 2020, compared with a 14-point surge in the previous five years. The stall coincides with a pause in the long-term decline of the Christian share of the population in the same places. This suggests that slowing secularisation is caused by fewer people leaving Christianity—rather than the growth of other faiths, such as Islam—alongside a surprising increase in Christian faith among younger people, particularly those from Generation Z (born between 1997 and 2012).

Education

11. Orwell’s 1984 now comes with ‘trigger warning’ (Telegraph)

George Orwell’s estate has been accused of attempting to censor 1984 by adding a “trigger warning” preface to a US edition of the dystopian novel.

The new introductory essay describes the novel’s protagonist Winston Smith as “problematic” and warns modern readers may find his views on women “despicable”.

Critics claim the preface, written by Dolen Perkins-Valdez, an American novelist, and included in the 75th anniversary edition published in the US last year, risks undermining the work’s warning against control of thought by the state.

In 1984, citizens of the superstate Oceania are punished for subversive thoughts by the Thought Police.

Now, in a real-world twist, the estate that oversees Orwell’s literary legacy stands accused of ideological policing.

“We’re getting somebody to actually convict George Orwell himself of thought crime in the introduction to his book about thought crime,” said Walter Kirn, a novelist and critic, on America This Week, a podcast hosted by journalist Matt Taibbi.

Enjoy your week!

The Curator